How does the use of jeans in fashion media connect to societal perceptions of class and identity?

This is an essay written for my journalism course. If you will spend some time to read it, please let me know what you think about it!

Throughout various eras and fashion models, denim jeans have been associated with different meanings. Initially, jeans were created as practical workwear in the mid-XIX, however the historical garment has grown to become a universal symbol of class and representation. Originally ideated by Levi Strauss for Californian miners, these trousers made of denim have certainly changed over the years, acquiring new cultural and social meanings. It is interesting to notice how jeans have been interpreted differently based on their cinematic context, reflecting and shaping the way in which society perceives them.

It does not come as a surprise that cinema, as a mirror and influencer of society, has used jeans as a powerful narrative and symbolic tool. As explained in the introduction of Media and Cultural Studies Key Works (2001), forms of media culture are pivotal in the building and shaping of social identities, and class representation and reproduction. The authors explain how narratives of media culture offer patterns of imposed behaviours and ideological influences, bypassing social and political standpoints hiding behind palatable forms of popular entertainment (Durham and Kellner, 2001, p. IX). Cinema has been one of the primary forms of media, which, with the employment of fashion, has changed the perception of an item’s social perception and symbolism.

This essay analyses how cinema utilises denim trousers to narrate stories and build its characters, through the examination of jeans’ symbolic significance related to social classes and ideologies. The analysis explores two different American movies as the main case studies: Norma Rae (1979), and Grease (1978). Through the two diverse narratives, it will be highlighted how the same fashion staple can signify and represent different aspirations and behaviours, and how this interchange in depiction is – more often than not – only permitted to the upper class.

Jeans as a costume in Cinema.

In cinema, jeans have never been a simple piece of wardrobe; instead, they represent a declaration of intentions. Initially associated with the working class, jeans have then been adopted by higher social classes, acquiring new meaning and losing gradually their exclusive connection to the manual labour. Since the 1920s, jeans began popping up in different films, especially Westerns. One example often mentioned by media and fashion journalists is The Untamed (1920), starring actor Tom Mix, who wears jeans to complete his cowboy appearance. Moving forward 30 years, we will find movies such as The Wild One (1953), starring Marlon Brando, and Rebel Without a Cause (1955), starring James Dean (Chilton, 2021).

Watching these movies illustrating different eras and characters, it is remarkable how jeans incorporated different meanings and how cinema changed the perception of society regarding those who wear them. Until the rise of the Western genre in cinema, jeans were predominately worn by people associated with labour. However, this narrative started to change, as people wanted to see themselves in the vest of their favourite characters (Shuck, 2013). This phenomenon is repeated again over the years, and through the different representations of people wearing this garment.

For example, in The Wild One in Figure 1 and Rebel Without a Cause in Figure 2, during the mid-1950s, jeans had adopted a completely different meaning. The characters wearing the denim trousers were written as rebellious and anti-conformists. These nuances were greatly appreciated by the middle-class youth, who sometimes wanted to distance themselves from their social class.

Despite jeans being transformed into a symbol of rebellion and a key element of youth identity, they almost continued to function as a “costume”. After Western movies, Americans who were not part of the working class adopted jeans almost exclusively as a fashion choice in their chosen environment. Similarly, after the rise of transgressive men on screen, middle-class individuals started wearing denim to abandon their social status for maybe half a day (Shuck, 2013). Nevertheless, it is clear that, even if jeans gained popularity among different social groups, they retained an air of subversion. In Class, Self, Culture (2004, p.100), Beverly Skeggs cites Anne Hollander (1988), explaining the meaning behind this behaviour, noting that “objects of clothing became invested with intangible and abstract elements of the moral and social order” (Hollander, 1988, cited in Skeggs, 2004, p.100). This statement has been true for most of fashion's history, where the working class has been depicted by individuals who do not live the same lifestyle but commodify the aesthetic to satisfy the middle and upper classes. This also applies to cinema.

The idea of jeans as a "costume" becomes even clearer when we consider how denim is marketed and consumed by those in more privileged social positions. Fashion advertising frequently constructs a romanticised image of the working class – think rugged cowboys, rebellious bikers, or carefree youths. These carefully crafted portrayals, often bearing little resemblance to the realities of working-class lives, offer consumers a chance to buy into a fantasy of rebellion or authenticity without requiring any real engagement with the social or economic challenges faced by those whose style they are adopting. Denim, originally born out of necessity, is transformed into a desirable object laden with imagined associations of freedom, individuality, and a romanticised working-class lifestyle. This process of turning a practical garment into a fashionable commodity deepens the divide: for some, denim remains a genuine reflection of their daily lives; for others, it’s a performance.

Case Study: Norma Rae (1979) – a symbol of working-class struggle.

Norma Rae is a drama directed by Martin Ritt (1979), which depicts the true story of a textile worker, Norma Rae Webster, who tries to unionise her workplace. In this movie, the denim jeans worn by the protagonist, played by Sally Field, is a symbol of her working-class identity and her struggle against exploitative labour practices. This representation resonates strongly with Marxist concepts of class struggle and alienation of labour. As Karl Marx (1867) argued, in capitalist societies, the working class (the proletariat) is forced to sell its labour power to the owning class (the bourgeoisie) in exchange for salaries. This system creates an inherently unequal relationship, where the workers are exploited for their labour and alienated from the products they produce. In Norma Rae, the textile mill is a microcosm of this capitalist system, with the mill owners representing the owning class, and the workers, like Norma Rae, being the proletariat.

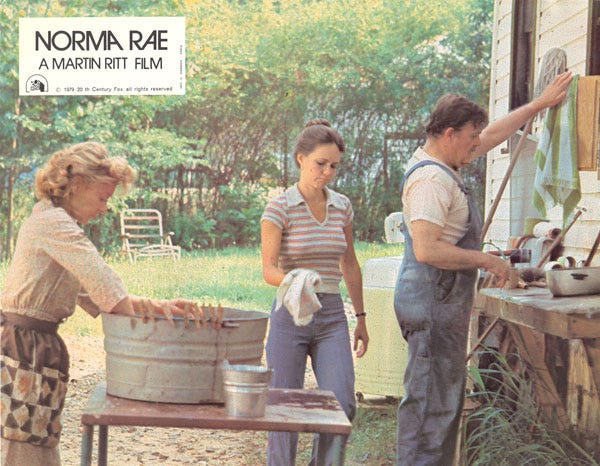

Contrary to the rebellious connotations of jeans applied to films like Rebel Without a Cause, in Norma Rae, the denim is firmly rooted in its original environment: practical workwear. In this context, the use of clothes aligns with Marx’s analysis of the material conditions of the working class, where garments serve primarily a utilitarian purpose dictated by the demands of their labour (Marx, 1867). Norma Rae is a worker single mother in a small town in the South of the US, and her jeans are certainly not a fashion statement or an option she adopted as a choice. As shown in Figure 3, Norma Rae’s outfit was not excessive nor something a fashion enthusiasm would aspire to achieve. The workers’ outfits were depicted as worn and faded, reflecting the harsh realities of her life and the economic hardships faced by her community.

The film’s costume design reinforces this connection between denim and working-class identity. Norma Rae’s wardrobe consists almost entirely of jeans, anonymous T-shirts, and dirty aprons, emphasising her lack of social mobility and the limited options available to her. While the movie effectively uses denim to symbolise working-class identity and struggle, it is important to acknowledge that such portrayals can be argued as potentially limiting and even stereotypical. In the first chapter of Class, Self, Culture, Skeggs (2004) illustrates the phenomenon of “Blaxploitation” films, a movie concept where black protagonists pose as the performance of their own stereotypes, caging the characters, and those whose represents, in a state of “blackness”. The author continues explaining that while black actors cannot perform “whiteness”, their counterparts, white characters, can attach and detach aspects of black culture and characteristics as and when appropriate (Skeggs, 2004, pp. 1-3). This analysis can apply also to the reproduction of working-class people, who are often written and displayed in ways that push existing stereotypes, which limit their representation to a set of visual and behavioural cues. In simple terms, the middle and upper classes can adopt elements of working-class style (like distressed denim or workwear) as fashion trends, effectively detaching these symbols from their original environment and meaning. While Norma Rae must wear these clothes as an indicator of her position, someone from a higher social class can wear the same clothes as a fashion statement, highlighting the difference between performance and reality.

Case Study: Grease (1978) - jeans as a rebellious statement

Following the popularity of stories like The Wild One and Rebel Without a Cause, jeans became associated with youth culture and a rejection of conformity (Shuck, 2013). This connection is also made in Grease, where denim is a key component of a distinct subculture. Grease, directed by Randal Kleiser (1978), is a musical set in the late 1950s about the lives of high school students at Rydell High. The movie focuses on the relationship between Danny Zuko, the leader of the "T-Birds" greaser gang, and Sandy Olsson, a sweet and innocent student. Additionally, with its narration, it explores themes of teenage rebellion, social groups, and the challenges of being a teenager in a post-war American society. What made this musical iconic in popular culture, is almost certainly its choreographies and fashion choices. In stark contrast to the utilitarian depiction of jeans in Norma Rae, Grease presents the trousers as a symbol of youthful rebellion and anti-conformism.

In Figure 4, it is noticeable how the meaning of the use of jeans is shifting, adapting to a different storyline. The fitting jeans worn by the T-Birds gang, often paired with a white T-shirt and leather jacket, are a costume choice designed to express a specific form of “masculinity” and rebellion against societal expectations. It is important to address that while the rebellion in Grease is presented as a challenge to social norms, it remains firmly within the confines of white, middle-class youth culture. Unlike Norma Rae, which focuses on the financial and social struggle of the working-class people, Grease centres on the exploration of identity and belonging within a social setting. The protagonists, in this instance, have the privilege to use clothing as a form of self-expression without the same economic constraints faced by Norma Rae. As shown in the picture above, these teenagers could choose between different jeans’ cuts and colours, a privilege that working class people are often denied in media representations, where clothing is more often a uniform of their class status.

Comparing these two cinematographic depictions can highlight how more privileged social classes can adopt elements of a “lower” class style without experiencing the same devaluation or stereotyping. In Norma Rae, denim is a marker of economic necessity and a symbol of working-class struggle. Consequently, it is tied to her social position. However, in Grease, jeans become a tool for self-expression and a symbol of youthful rebellion, albeit within a more privileged context. The same piece of clothing takes on vastly different meanings depending on the social and narrative context in which it is presented. Perhaps this reinforces the idea that the meaning of clothing is not inherent but is constructed through social and cultural practices.

Furthermore, the "performance" aspect of clothing, as discussed in relation to Skeggs' work (2004), is particularly relevant here. The characters in Grease actively perform a particular identity through their clothing choices. They are consciously adopting a style that signifies their belonging to a specific group and their rejection of mainstream norms. This performance is a form of self-fashioning, a way for the characters to assert their individuality and agency. This stands in stark contrast to the forced performance of class seen in Norma Rae, where clothing is less a choice and more a consequence of economic circumstances. Norma Rae's clothing is not a performance of choice but a reflection of her material reality. This difference exemplifies how the same garment, jeans, can be used to perform vastly different aspects of identity depending on the wearer's social position. The characters in Grease perform "working class" aesthetics as a form of play, while for Norma Rae, it is a daily lived reality. In her work, Skeggs (2004, pp. 139) utilises a study conducted by Strathern (1991; 1992a) and explained by Munro (1996), which can highlight the reason why the stereotypical depiction of classes can be harmful to those who already live in disadvantaged.

“Her point is that the middle classes move from figure to figure, attaching and detaching in their self-performance, and crucially, as Munro suggests, perception of the second figure involves forgetting part of the first figure. There is never a whole, selves are always in extension. Munro warns against reading this in a realist way, as if a core self appropriates a range of identities, assuming that there is a true self to which one can return. He argues that, in the process of extension, one never travels out of place (that is the core self), rather the only movement is circular, from one figure to another” (Skeggs, 2004, pp. 139-140).

To summarise, the contrast between Norma Rae and Grease’s costume choices shows how the same garment can be used to represent vastly different social experiences and ideologies, highlighting the complex and unequal relationship between clothing, identity, and social class. However, only one of the two mentioned classes can afford the pleasure of returning to a more privileged association whenever it decides to return to its roots and discontinue the performance of a likeable character.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this essay has explored the multifaced symbolism of denim jeans in cinema, demonstrating the ways in which the garment can be linked to complex meanings related to social class, identity, and ideology. Through the analysis of Norma Rae and Grease, it becomes clear that the meaning of denim is not fixed but rather fluid and context-dependent, shaped by the narrative, the characters, and the broader social landscape.

On one hand, in Norma Rae, denim serves as a potent symbol of working-class struggle and financial hardship. The protagonist’s jeans are not a fashion statement but a reproduction of her material reality, a uniform of her labour within a capitalist system. This image, while effectively conveying the challenges faced by working-class individuals, also risks reducing their identity to a single, class-based stereotype. On the other hand, Grease presents denim as a manifestation of youth and self-expression within privileged, middle-class spaces. The characters in the musical, actively perform a particular identity through their clothing choices, using denim as a tool for fashion exploration and asserting their agency. However, this performance, is fundamentally different from the forced performance of class seen in Norma Rae. The teenagers in Grease can adopt the appearance of the lower class to cosplay as transgressive individuals while still maintaining their social status. Differently, working-class individuals like Norma Rae are often confined to a strict set of behaviours and styles and cannot selectively appropriate and discard elements of middle or upper-class style, as it wouldn’t conform to the stereotypical illustrations of their persona.

Ultimately, the contrasting uses of denim in Norma Rae and Grease reveal the complex and unequal relationship between clothing, identity, and social class in cinema. While denim began as a purely functional garment for the working class, its meaning has evolved and diversified over time, becoming a powerful tool for expressing a range of social and cultural messages. However, as these case studies demonstrate, not all wearers of denim are created equal. The ability to manipulate and control the meaning of this iconic garment remains largely a privilege of the socially and economically advantaged, further perpetuating the very inequalities that cinema often purports to represent

Bibliography

Chilton, C. (2021). 40 Iconic Denim Moments in Movie History. [online] Harper’s BAZAAR. Available at: https://www.harpersbazaar.com/culture/film-tv/g37232033/denim-movie-moments/ [Accessed 20 Jan. 2025].

Durham, M.G. and Kellner, D.M. (2001). Adventures in Media and Cultural Studies: Introducing the KeyWorks . In: Media and Cultural Studies Key Works. [online] Blackwell Publishing, p.IX. Available at: https://we.riseup.net/assets/102142/appadurai.pdf [Accessed 20 Jan. 2025].

Marx, K. (1867). Capital - A Critique of Political Economy. English ed. [online] Engels Internet Archive. Available at: https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1867-c1/ch01.htm#S4 [Accessed 15 Nov. 2024].

Shuck, D. (2013). A Cinematic History of Denim. [online] Heddels. Available at: https://www.heddels.com/2013/04/a-cinematic-history-of-denim/ [Accessed 19 Jan. 2025].

Skeggs, B. (2004). Class, Self, Culture. [online] London: Routledge. Available at: https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/ual/reader.action?docID=1543047&query=skeggs&ppg=8# [Accessed 20 Jan. 2025].

Love this in-depth analysis! Very well written, and I appreciated the choice of considering films and costumes to further contextualise your point. Good job!